Taylor Naftali

As-Builts

This project begins with a competition brief calling for the transformation of a ruined Tuscan estate through adaptive reuse. Rather than treat the ruin as a problem to be redesigned, I chose to treat it as a site to be read — a drawing problem before it’s a design problem.

The estate has lived many lives — patchings, renovations, erasures. By tracing these conditions, both literally and interpretively, my project surfaces those histories rather than overwriting them. It does not restore the house to a previous state, but instead acknowledges the layered, uneven, and incomplete nature of its current one. What remains becomes material — not just physically, but representationally.

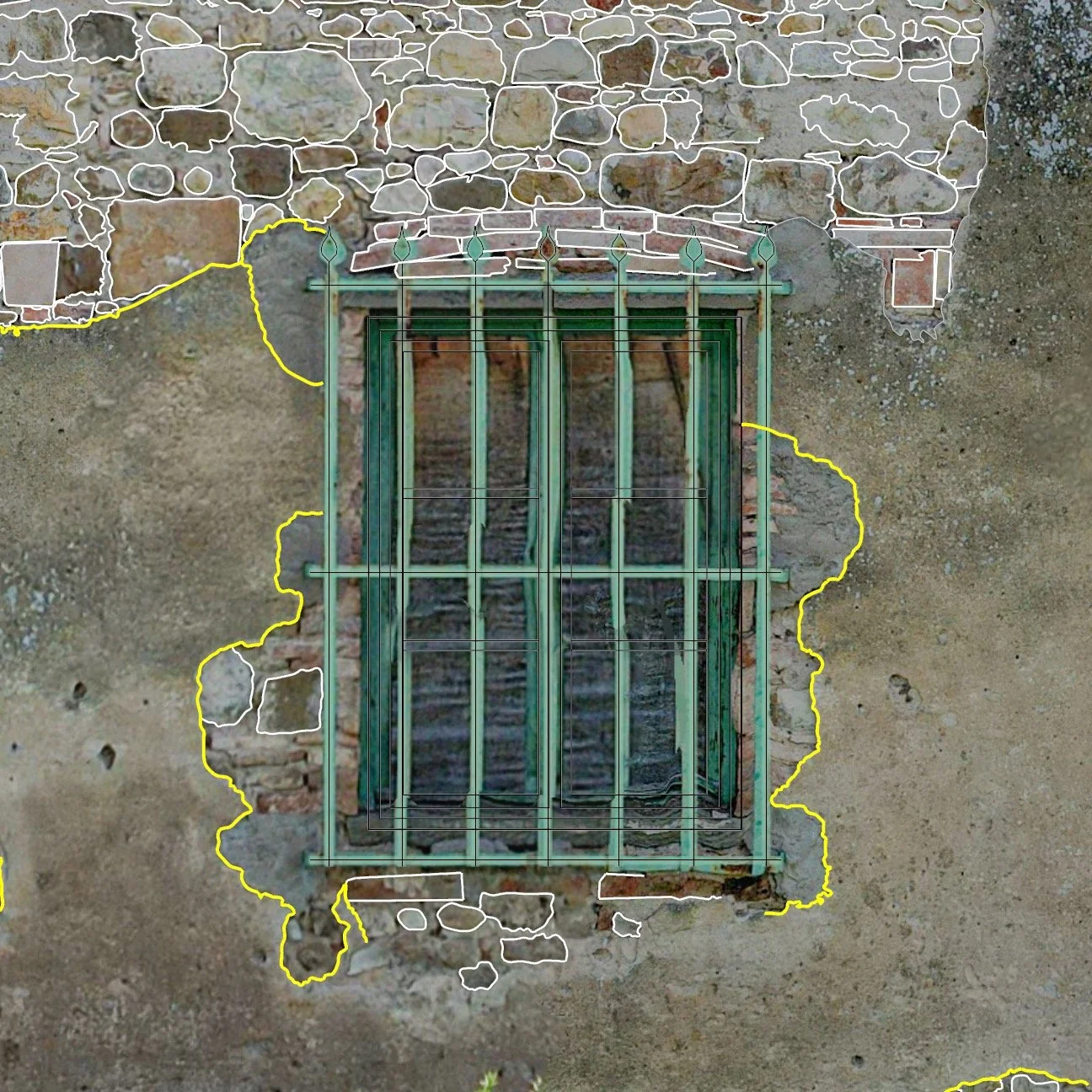

The core of the work is drawing — not just as representation, but as investigation. I began by tracing the competition’s photographs and comparing them to floor plans and elevations. These images were not true orthographics; they contained perspective and distortion. Stones appeared pixelated, ground lines unclear, windows sealed or resized. To draw them meant to make decisions — to design in the act of documentation.

These acts revealed something larger: all architectural drawing carries authorship. We’re taught to document with precision, but not necessarily truth, often drawing things as they “should be” rather than as they are.

Authorship emerges in choices: estimating pixelated stones, deciding where to place the ground line, or whether narrow elements deserve a single line or two. Perspective in the photos forces inferences.

Architectural intuition also shapes interpretation. Tracing windows, I noticed inconsistencies — yet experience tells me windows are often standardized. Discrepancies of a few inches may be illusion, not fact.

My line drawings lean into these ambiguities. Are irregularities errors or evidence? Do we trust the photograph, or our architectural knowledge? In documenting, the act of drawing becomes a speculative proposal in itself.